Creating an E-Mentoring Community: How DO-IT does it, and how you can do it, too

Creating an E-Mentoring Community: How DO-IT does it, and how you can do it too is available in HTML and PDF versions. For the HTML version, follow the table of contents below. For the PDF version, go to Creating an E-Mentoring Community - PDFs.

© 2006 University of Washington

This material is based upon work supported by The Mitsubishi Electric America Foundation and the National Science Foundation (cooperative agreement #HRD-0227995). Any opinions, findings, and conclusion or recommendations expressed in this material do not necessarily represent the policy of the funding sources, and you should not assume their endorsement.

Dedication

This book is dedicated to college-bound teens who are smart enough to know they can learn from the experiences of others.

It is also dedicated to mentors who find joy in knowing they've made a difference in a young person's life. These caring adults may mentor a child as part of their relationship as:

- a parent who is continually learning how best to guide his or her child toward a happy, self-determined life

- a teacher who is learning strategies to apply in the special education or inclusive classroom

- a counselor or group leader who is open to new ideas for helping young people become successful adults

The book is written for those who wish to develop an online community that facilitates mentoring, peer support, and other activities to promote academic and career success, social competence, self-determination, and leadership skills for teens with a wide range of abilities and disabilities. Anyone who enjoys hearing about the goals, challenges, efforts, experiences, and insights of young people facing life's challenges will also enjoy reading this book.

Acknowledgments

Author, Contributors, Funders

Courage is not the absence of fear;

it is the making of action in spite of fear.— M. Scott Peck —

The Author

Dr. Sheryl Burgstahler is the founder and director of DO-IT (Disabilities, Opportunities, Internetworking, and Technology) at the University of Washington. DO-IT promotes the success of people with disabilities in postsecondary academic programs and careers. It sponsors projects that increase the use of assistive technology and stimulate the development of accessible facilities, computer labs, electronic resources in libraries, web pages, educational multimedia, and Internet-based distance learning programs.

Dr. Burgstahler is the director of the Northwest Center on Access to Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (AccessSTEM), funded by the National Science Foundation (cooperative agreement #HRD-0227995) to increase the participation of people with disabilities in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) careers. She codirects the National Center on Accessible Information Technology in Education (AccessIT), funded by the National Institute on Rehabilitation Research of the U.S. Department of Education (grant #H133D010306) to coordinate a nationwide effort to promote the use of accessible information technology. She also codirects The Alliance for Access to Computing Careers (AccessComputing), funded by the National Science Foundation (grant #CNS-0540615) to increase the participation of people with disabilities in computing fields.

Dr. Burgstahler has published dozens of articles and delivered presentations at national and international conferences that focus on the full inclusion of individuals with disabilities in postsecondary education, distance learning, work-based learning, and electronic communities. She is the author or coauthor of six books on using the Internet with precollege students. Dr. Burgstahler has extensive experience teaching at the precollege, community college, and university levels. She is the director of Accessible Technology Services within Computing & Communications and Affiliate Associate Professor in the College of Education at the University of Washington. More about Dr. Burgstahler can be found on her website.

The Contributors

Thanks to the more than one hundred successful young people and adults with disabilities for sharing insights and advice that guided the development of this book. Special thanks to Randy Hammer, Jessie Shulman, Larry Scadden, and Todd Stabelfeldt for sharing their personal stories and to Carole Isakson for conducting interviews and assisting with editing. In addition, for contributing to the content and editing of the book, thanks go to Scott Bellman, Beverly Biderman, Tresa Bos, Dan Comden, Lyla Crawford, Deb Cronheim, Tanis Doe, Nan Hawthorne, Doug Hayman, Natalie Hilzen, Phyllis Levine, Hope Long, Sara Lopez, Kathryn Pope Olson, Lynda Price, Mary Proudfoot, Michael Richardson, Nancy Rickerson, Amy Schieffer, Lisa Stewart, Mark Uslan, Aimee Verrall, Teresa Welley, and Sue Wozniak.

Some of the content of this book was adapted from the comprehensive collection of DO-IT publications at www.washington.edu/doit. Readers will find there some of the same content adapted for different audiences, as well as other publications, videos, and resources that promote the success of people with disabilities and the use of technology as an empowering tool. The most relevant references can be found in Chapter Fourteen of this book.

The Funding Sources

Partial funding for the creation of this book was provided by the Mitsubishi Electric America Foundation, a nonprofit foundation jointly funded by Mitsubishi Electric Corporation of Japan and its American affiliates. The Foundation's mission is to contribute to a better world for us all by helping young people with disabilities, through technology, maximize their potential and participation in society. Additional funding was provided by the National Science Foundation (cooperative agreement #HRD-0227995). Any questions, findings, or conclusions expressed in these materials are those of the author and other contributors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding agencies.

Foreword

We must take control of our own destiny, but we must avoid alienating

those who may be gatekeepers to future success.— Dr. Lawrence Scadden —

When and how did I learn to take charge of my own life? People who know me may think that I have always had self-determination: I have had a successful career moving from place to place, job to job, going where there were exciting new opportunities. That was not always the case!

As a teenager, my first love was science and mathematics. I wanted to become a scientist or engineer, but teachers, counselors, and family urged me to reconsider, saying, "There is no place for a blind person in these fields." I believed them. Not until my early twenties did I take charge of my own life and make a plunge into science. I was in graduate school working on an advanced degree in government studies and teaching part-time in a community college when I began taking courses at a nearby college looking for an area of science in which I could make a mark. Human perception was the answer. Most of the scientific literature on human perception dealt with vision, leaving important research on touch and hearing for others, like me. I changed my field, and my life changed forever.

When reading this exciting new volume, Creating an E-Mentoring Community, I recognized that many of the young people who contributed to the book achieved self-determination as teens. Why did they succeed at that age when I did not? Many good reasons explain the difference. In the 1950s when I was a teenager, those of us with disabilities had few role models to look to for guidance, and we had few opportunities to learn and demonstrate our capabilities and interests. Today many opportunities exist, and information regarding successful people with disabilities can be disseminated far more easily than in the past. The young people who contributed to this volume all were involved in exemplary programs that promoted self-esteem and fostered self-determination. Reading about their experiences and examining their advice, I am aware of the similarities and the differences between opportunities of today and those of my era. For instance, the factors that promote success and achieving self-determination are quite similar.

Todd, in an E-Community Activity in Chapter Four, says that one's attitude and personality are key factors for success. I agree even though these personal traits can be pretty rough around the edges sometimes; persistence may be only a shade away from being stubborn or obstinate. A balanced approach in human relations is important, although often difficult to manage. We must take control of our own destiny, but we must avoid alienating those who may be gatekeepers to future success.

Todd and Randy commend their parents for expressing high expectations for them and their lives early on. I do too, but, as this book points out, many people with disabilities achieve self-determination without parental support. It is possible, but it is much easier when one's own attitude regarding future success is learned early from one's family.

Jessie says that successful people need to be resourceful and adaptable. I continue to find that to be good advice every time I tackle a new challenge. People with disabilities are often pioneers, moving into new arenas where few can give advice. We must turn to our own strengths to solve problems of access and to perform tasks independently when necessary.

Randy says that it is important to be resilient. Oh yes! Mistakes, failures, and negative attitudes may seem to be barriers to forward motion, but we cannot let these deter our progress. Resilience is an important trait we need to have working for us all the time.

The primary difference for today's young people with disabilities from that known by those of us from an earlier generation relates to the opportunities and the information available today that promote personal growth. Most of the contributors to this book are participants in DO-IT programs or projects funded by the Mitsubishi Electric America Foundation and the National Science Foundation. Both of these programs are dedicated to giving young people with disabilities the opportunity to learn and to develop skills that will help them find their own accommodations and to be active and productive members of our communities. They learned early in their lives that their abilities are far more important than their disabilities. They serve as role models for each other, but they learn about others with disabilities who have gone before and who are successful in a myriad of careers and avocations. These are experiences and data that combine to produce knowledge, and knowledge is power.

The ideal would be to allow all young people with disabilities to have these opportunities, but that is not the reality. The next best thing is to provide more and more of these young people with the experiences vicariously through sharing the words of many who have had opportunities to participate in these exemplary programs. This volume—combined with the intervention of parents, teachers, and mentors—can provide these vicarious experiences for thousands of other young people with disabilities. Young people are heard sharing their insights and advice on achieving success. All of them have disabilities and have conquered them.

The contributions from these individuals are quite poignant, but the book contains other valuable guides for parents, teachers, mentors, and people with disabilities themselves. The author, Sheryl Burgstahler, has applied her wealth of knowledge and experience gained through years of working with people with disabilities to assembling a wealth of activities that will help all readers to interact with the information presented by the contributors. Readers, then, can take new skills and ideas to help them as they work with other young people who have disabilities.

The book's contributors, along with the author, strongly promote the concept that people with disabilities and their parents, teachers, and mentors all must profess and maintain high expectations for the person with a disability. It was gratifying to read this over and over in the book because it echoes something I have used to conclude dozens of public presentations over the last twenty years. I have numerous opportunities to address gatherings of people with disabilities and others who have contact with them. Often I talk about my own life experiences, urging others to help people with disabilities attain the same success. My concluding remarks frequently follow this theme. Speaking first to people with disabilities, I say, "Come fly with me; let your expectations soar!" Then to their parents, teachers, and counselors I say, "Come fly with them; let your expectations for them soar! Give them the opportunities and the tools to let them achieve their goals." Finally, to everyone else I say, "Come fly with us! Let our expectations for all people with disabilities soar!" This book is a tool that can raise expectations for all readers.

Lawrence A. Scadden, Ph.D.

Retired Program Officer, National Science Foundation (NSF)

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Life is a succession of lessons, which must be lived to be understood.

— Ralph Waldo Emerson —

Table of Contents

- Overview of this Book

- History and Current Trends Regarding People with Disabilities

- DO-IT

- The Role of Technology in Creating this Book

- What You'll Find in this Book

- How to Use this Book

- How to Download or Purchase this Book and Complementary Videos

PART I: Creating an Electronic Mentoring Community

Chapter One: An Introduction to E-mentoring and E-communities

- Peer, Near-Peer, and Mentor Support

- Computer-Mediated Communication

- E-Mentoring Communities

- DO-IT's E-Mentoring Community

- Joining an Existing Online Mentoring Program

Chapter Two: Steps to Creating an E-mentoring Community

- Establish clear goals for the program.

- Decide what technology to use.

- Establish a discussion group structure.

- Select an administrator for the e-mentoring community, and make other staff and volunteer assignments as needed.

- Develop guidelines for protégés concerning appropriate and safe Internet communications.

- Establish roles and develop guidelines, orientation, and training for mentors.

- Standardize procedures for recruiting and screening mentor applicants.

- Determine how to recruit protégés.

- Provide guidance to parents.

- Establish a system whereby new mentors and protégés are introduced to community members.

- Provide ongoing supervision of and support to mentors.

- Monitor and manage online discussions.

- Share resources.

- Employ strategies that promote personal development.

- Publicly share the value and content of communications in the e-mentoring community and the contributions of the mentors.

- Monitor the workings of the e-mentoring community as it evolves. Adjust procedures and forms accordingly.

- Have fun!

Chapter Three: Orientation and Training for Mentors

- Mentor Tip: Orientation

- Mentor Tip: Discussion Lists/Forums

- Mentor Tip: Mentoring Guidelines

- Mentor Tip: Communication of Emotions

- Mentor Tip: Positive Reinforcement

- Mentor Tip: Listening Skills

- Mentor Tip: Questions for Protégés

- Mentor Tip: Disabilities

- Mentor Tip: Guiding Teens

- Mentor Tip: Conversation Starters

- Mentor Tip: "Dos" when Mentoring Teens

- Mentor Tip: "Don'ts" when Mentoring Teens

Chapter Four: Introduction to Mentoring for Success and Self-Determination

- E-Community Activity: Welcome to Online Mentoring

- E-Community Activity: Guidelines for Protégés

- E-Community Activity: Safety on the Internet

- E-Community Activity: Jessie and Learning Strategies

- E-Community Activity: Jessie and Disability Benefits

- E-Community Activity: Randy and Proving Yourself

- E-Community Activity: Randy and Taking on Challenges

- E-Community Activity: Advice from Randy

- E-Community Activity: Todd and an Awkward Moment

- E-Community Activity: Todd, Family, and Friends

- E-Community Activity: Jessie, Randy, Todd, and Success Strategies

- E-Community Activity: Jessie, Randy, Todd, and Awkward Situations

- Mentor Tip: Success

- E-Community Activity: Emulating Characteristics of Successful People

- E-Community Activity: Achieving Success

- Mentor Tip: Self-Determination

- E-Community Activity: Defining Self-Determination

- E-Community Activity: Characteristics of Self-Determined People

- E-Community Activity: Steps Toward Self-Determination

- Mentor Tip: Commitment to Learning

- Mentor Tip: Positive Values

- Mentor Tip: Social Competencies

- Mentor Tip: Positive Identity

- Mentor Tip: Self-Development

- Mentor Tip: Problem Solving

- E-Community Activity: Advice from Teens

- E-Community Activity: Success Stories on the Web

- E-Community Activity: Affirming Success

PART II: Supporting Teens in an E-Mentoring Community

Chapter Five: Define Success for Yourself

- Mentor Tip: Steps to Success

- Mentor Tip: Definition of Success

- E-Community Activity: Learning from Successful Experiences

- E-Community Activity: Finding Your Goals for Success

- E-Community Activity: Learning from Teens with Disabilities

- E-Community Activity: Learning from Role Models

- E-Community Activity: Discovering Academic Success Factors

- E-Community Activity: Selecting Your Best Teacher

- E-Community Activity: Defining Success

- Mentor Tip: Keeping a Positive Attitude

- E-Community Activity: Building a Positive Attitude

- E-Community Activity: Finding Humor

- E-Community Activity: Affirming Success

Chapter Six: Set Personal, Academic, and Career Goals. Keep Your Expectations High

- Mentor Tip: Goals

- Mentor Tip: Goal Setting

- E-Community Activity: Setting Goals

- Mentor Tip: Promoting High Expectations

- Mentor Tip: Getting Help with Setting Goals

- E-Community Activity: Getting Help to Maintain High Expectations

- E-Community Activity: Matching Academic Interests with Careers

- Mentor Tip: People with Disabilities and STEM

- E-Community Activity: Pursuing STEM

- E-Community Activity: Considering College Options

- E-Community Activity: Making Plans

- E-Community Activity: Affirming Success

Chapter Seven: Understand Your Abilities and Disabilities; Play to Your Strengths

- Mentor Tip: Disability Acceptance

- E-Community Activity: Accepting Disability

- Mentor Tip: Labels

- E-Community Activity: Trying New Things

- E-Community Activity: Identifying Your Likes and Dislikes

- Mentor Tip: Incorrect Assumptions

- E-Community Activity: Dealing with Incorrect Assumptions

- E-Community Activity: Describing Your Disability

- E-Community Activity: Dealing with Rude People

- E-Community Activity: Thinking about Language

- E-Community Activity: Responding to Labels

- E-Community Activity: Building on Strengths

- E-Community Activity: Redefining Limitations as Strengths

- E-Community Activity: Exploring Learning Strengths and Challenges

- E-Community Activity: Taking Inventory of Your Learning Style

- E-Community Activity: Finding Careers That Use Your Skills

- E-Community Activity: Matching Skills with Careers

- E-Community Activity: Identifying Your Career Interests and Work Style

- E-Community Activity: Healthy Self-Esteem

- E-Community Activity: Valuing Yourself

- E-Community Activity: Learning to Value Yourself

- E-Community Activity: Affirming Self-Value

- E-Community Activity: Affirming Success

Chapter Eight: Develop Strategies to Reach Your Goals

- Mentor Tip: Self-Advocacy

- Mentor Tip: Goals

- Mentor Tip: Short- and Long-Term Goals

- E-Community Activity: Making Informed Decisions

- Mentor Tip: Rights and Responsibilities

- E-Community Activity: Knowing Your Rights and Responsibilities in College

- E-Community Activity: Securing Accommodations in College

- E-Community Activity: Developing Study Habits

- E-Community Activity: Creating Win-Win Solutions

- E-Community Activity: Changing Advocacy Roles

- E-Community Activity: Self-Advocating

- E-Community Activity: Self-Advocating with Teachers

- E-Community Activity: Disclosing Your Disability in College

- E-Community Activity: Disclosing Your Disability to an Employer

- E-Community Activity: Advising a Friend about Disability Disclosure

- E-Community Activity: Being Assertive

- E-Community Activity: Securing Job Accommodations

- E-Community Activity: Asking for Accommodations at Work

- E-Community Activity: Standing Up for Convictions and Beliefs

- E-Community Activity: Learning from Mistakes

- E-Community Activity: Affirming Success

Chapter Nine: Use Technology as an Empowering Tool

- E-Community Activity: Surveying Accessible Technology

- Mentor Tip: Promoting Technology

- Mentor Tip: Technology Access

- Mentor Tip: Technology and Success in School

- E-Community Activity: Becoming Digital-Age Literate

- E-Community Activity: Using Technology with Young Children

- E-Community Activity: Using Technology for Success in School

- E-Community Activity: Using Technology to Complete Homework

- E-Community Activity: Using Technology in Science and Engineering

- E-Community Activity: Surfing the Web to Prepare for College

- E-Community Activity: Using Technology in Your Career

- E-Community Activity: Using Technology in Careers

- E-Community Activity: Surfing the Web to Prepare for a Career

- E-Community Activity: Using Technology to Enhance Your Social Life

- E-Community Activity: Affirming Success with Technology

Chapter Ten: Work Hard; Persevere; Be flexible

- Mentor Tip: Actions to Achieve Goals

- E-Community Activity: Working Hard

- E-Community Activity: Coping with Stress

- E-Community Activity: Being Flexible

- E-Community Activity: Taking Risks

- E-Community Activity: Taking Action

- E-Community Activity: Learning from Experiences

- E-Community Activity: Learning from Work Experiences

- E-Community Activity: Understanding the Value of Work Experiences

- E-Community Activity: Being Resilient

- E-Community Activity: Affirming Success

Chapter Eleven: Develop a Support Network. Look to Family, Friends, and Teachers

- Mentor Tip: Teen Support

- Mentor Tip: Supportive Environment

- Mentor Tip: Self-Determination Support

- Mentor Tip: Teen Relationships with Adults

- E-Community Activity: Developing Relationships with Adults

- E-Community Activity: Working with Adults

- E-Community Activity: Participating in Activities

- E-Community Activity: Being a Good Friend

- Mentor Tip: Friendships

- E-Community Activity: Developing Friendships

- E-Community Activity: Locating a Career OneStop

- E-Community Activity: Finding Resources and Support

PART III: Where to Go from Here

Chapter Twelve: Share Your Story

- E-Community Activity: Share Your Views on Success

- E-Community Activity: Share Your Views on Goals

- E-Community Activity: Share Your Views on Abilities

- E-Community Activity: Share Your Views on Strategies

- E-Community Activity: Share Your Views on Technology

- E-Community Activity: Share Your Views on Working Hard

- E-Community Activity: Share Your Views on Support Network

Chapter Thirteen: Sample Documents

- Sample Mentor Guidelines

- Sample Protégé Guidelines

- Sample Mentor Application

- Sample Parent/Guardian Consent

Chapter Fourteen: Resources and Bibliography

© 2007 University of Washington

Permission is granted to copy these materials for non-commercial purposes provided the source is acknowledged.

Creating an E-Mentoring Community

How DO-IT does it, and how you can do it, too

Introduction - 1759 KB

Includes

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Overview of this Book

- History and Current Trends Regarding People with Disabilities

- DO-IT

- The Role of Technology in Creating this Book

- What You'll Find in this Book

- How to Use this Book

- How to Download or Purchase this Book and Complementary Videos.

Chapter 1 - 1385 KB

Includes

- PART I: CREATING AN ELECTRONIC MENTORING COMMUNITY

- Chapter One: An introduction to e-mentoring and e-communities.

- Peer, Near-Peer, and Mentor Support

- Computer-Mediated Communication

- E-Mentoring Communities

- DO-IT's E-Mentoring Community

- Joining an Existing Online Mentoring Program

Chapter 2 - 1125 KB

Includes

- Chapter Two: Steps to creating an e-mentoring community.

- Establish clear goals for the program.

- Decide what technology to use.

- Establish a discussion group structure.

- Select an administrator for the e-mentoring community, and make other staff and volunteer assignments as needed.

- Develop guidelines for protégés concerning appropriate and safe Internet communications.

- Establish roles and develop guidelines, orientation, and training for mentors.

- Standardize procedures for recruiting and screening mentor applicants.

- Determine how to recruit protégés.

- Provide guidance to parents.

- Establish a system whereby new mentors and protégés are introduced to community members.

- Provide ongoing supervision of and support to mentors.

- Monitor and manage online discussions.

- Share resources.

- Employ strategies that promote personal development.

- Publicly share the value and content of communications in the e-mentoring community and the contributions of the mentors.

- Monitor the workings of the e-mentoring community as it evolves.

- Adjust procedures and forms accordingly.

- Have fun!

Chapter 3 - 551 KB

Includes

- Chapter Three: Orientation and training for mentors.

- Mentor Tip: Orientation

- Mentor Tip: Discussion Lists/Forums

- Mentor Tip: Mentoring Guidelines

- Mentor Tip: Communication of Emotions

- Mentor Tip: Positive Reinforcement

- Mentor Tip: Listening Skills

- Mentor Tip: Questions for Protégés

- Mentor Tip: Disabilities

- Mentor Tip: Guiding Teens

- Mentor Tip: Conversation Starters

- Mentor Tip: "Dos" when Mentoring Teens

- Mentor Tip: "Don'ts" when Mentoring Teens

Chapter 4 - 755 KB

Includes

- Chapter Four: Introduction to mentoring for success and self-determination.

- E-Community Activity: Welcome to Online Mentoring

- E-Community Activity: Guidelines for Protégés

- E-Community Activity: Safety on the Internet

- E-Community Activity: Jessie and Learning Strategies

- E-Community Activity: Jessie and Disability Benefits

- E-Community Activity: Randy and Proving Yourself

- E-Community Activity: Randy and Taking on Challenges

- E-Community Activity: Advice from Randy

- E-Community Activity: Todd and an Awkward Moment

- E-Community Activity: Todd, Family, and Friends

- E-Community Activity: Jessie, Randy, Todd, and Success Strategies

- E-Community Activity: Jessie, Randy, Todd, and Awkward Situations

- Mentor Tip: Success

- E-Community Activity: Emulating Characteristics of Successful People

- E-Community Activity: Achieving Success

- Mentor Tip: Self-Determination

- E-Community Activity: Defining Self-Determination

- E-Community Activity: Characteristics of Self-Determined People

- E-Community Activity: Steps Toward Self-Determination

- Mentor Tip: Commitment to Learning

- Mentor Tip: Positive Values

- Mentor Tip: Social Competencies

- Mentor Tip: Positive Identity

- Mentor Tip: Self-Development

- Mentor Tip: Problem Solving

- E-Community Activity: Advice from Teens

- E-Community Activity: Success Stories on the Web

- E-Community Activity: Affirming Success

Chapter 5 - 658 KB

Includes

- PART II: SUPPORTING TEENS IN AN E-MENTORING COMMUNITY

- Chapter Five: Define success for yourself.

- Mentor Tip: Steps to Success

- Mentor Tip: Definition of Success

- E-Community Activity: Learning from Successful Experiences

- E-Community Activity: Finding Your Goals for Success

- E-Community Activity: Learning from Teens with Disabilities

- E-Community Activity: Learning from Role Models

- E-Community Activity: Discovering Academic Success Factors

- E-Community Activity: Selecting Your Best Teacher

- E-Community Activity: Defining Success

- Mentor Tip: Keeping a Positive Attitude

- E-Community Activity: Building a Positive Attitude

- E-Community Activity: Finding Humor

- E-Community Activity: Affirming Success

Chapter 6 - 723 KB

Includes

- Chapter Six: Set personal, academic, and career goals. Keep your expectations high.

- Mentor Tip: Goals

- Mentor Tip: Goal Setting

- E-Community Activity: Setting Goals

- Mentor Tip: Promoting High Expectations

- Mentor Tip: Getting Help with Setting Goals

- E-Community Activity: Getting Help to Maintain High Expectations

- E-Community Activity: Matching Academic Interests with Careers

- Mentor Tip: People with Disabilities and STEM

- E-Community Activity: Pursuing STEM

- E-Community Activity: Considering College Options

- E-Community Activity: Making Plans

- E-Community Activity: Affirming Success

Chapter 7 - 784 KB

Includes

- Chapter Seven: Understand your abilities and disabilities. Play to your strengths.

- Mentor Tip: Disability Acceptance

- E-Community Activity: Accepting Disability

- Mentor Tip: Labels

- E-Community Activity: Trying New Things

- E-Community Activity: Identifying Your Likes and Dislikes

- Mentor Tip: Incorrect Assumptions

- E-Community Activity: Dealing with Incorrect Assumptions

- E-Community Activity: Describing Your Disability

- E-Community Activity: Dealing with Rude People

- E-Community Activity: Thinking about Language

- E-Community Activity: Responding to Labels

- E-Community Activity: Building on Strengths

- E-Community Activity: Redefining Limitations as Strengths

- E-Community Activity: Exploring Learning Strengths and Challenges

- E-Community Activity: Taking Inventory of Your Learning Style

- E-Community Activity: Finding Careers That Use Your Skills

- E-Community Activity: Matching Skills with Careers

- E-Community Activity: Identifying Your Career Interests and Work Style

- E-Community Activity: Healthy Self-Esteem

- E-Community Activity: Valuing Yourself

- E-Community Activity: Learning to Value Yourself

- E-Community Activity: Affirming Self-Value

- E-Community Activity: Affirming Success

Chapter 8 - 498 KB

Includes

- Chapter Eight: Develop strategies to reach your goals.

- Mentor Tip: Self-Advocacy

- Mentor Tip: Goals

- Mentor Tip: Short- and Long-Term Goals

- E-Community Activity: Making Informed Decisions

- Mentor Tip: Rights and Responsibilities

- E-Community Activity: Knowing Your Rights and Responsibilities in College

- E-Community Activity: Securing Accommodations in College

- E-Community Activity: Developing Study Habits

- E-Community Activity: Creating Win-Win Solutions

- E-Community Activity: Changing Advocacy Roles

- E-Community Activity: Self-Advocating

- E-Community Activity: Self-Advocating with Teachers

- E-Community Activity: Disclosing Your Disability in College

- E-Community Activity: Disclosing Your Disability to an Employer

- E-Community Activity: Advising a Friend about Disability Disclosure

- E-Community Activity: Being Assertive

- E-Community Activity: Securing Job Accommodations

- E-Community Activity: Asking for Accommodations at Work

- E-Community Activity: Standing Up for Convictions and Beliefs

- E-Community Activity: Learning from Mistakes

- E-Community Activity: Affirming Success

Chapter 9 - 653 KB

Includes

- Chapter Nine: Use technology as an empowering tool.

- E-Community Activity: Surveying Accessible Technology

- Mentor Tip: Promoting Technology

- Mentor Tip: Technology Access

- Mentor Tip: Technology and Success in School

- E-Community Activity: Becoming Digital-Age Literate

- E-Community Activity: Using Technology with Young Children

- E-Community Activity: Using Technology for Success in School

- E-Community Activity: Using Technology to Complete Homework

- E-Community Activity: Using Technology in Science and Engineering

- E-Community Activity: Surfing the Web to Prepare for College

- E-Community Activity: Using Technology in Your Career

- E-Community Activity: Using Technology in Careers

- E-Community Activity: Surfing the Web to Prepare for a Career

- E-Community Activity: Using Technology to Enhance Your Social Life

- E-Community Activity: Affirming Success with Technology

Chapter 10 - 489 KB

Includes

- Chapter Ten: Work hard. Persevere. Be flexible.

- Mentor Tip: Actions to Achieve Goals

- E-Community Activity: Working Hard

- E-Community Activity: Coping with Stress

- E-Community Activity: Being Flexible

- E-Community Activity: Taking Risks

- E-Community Activity: Taking Action

- E-Community Activity: Learning from Experiences

- E-Community Activity: Learning from Work Experiences

- E-Community Activity: Understanding the Value of Work Experiences

- E-Community Activity: Being Resilient

- E-Community Activity: Affirming Success

Chapter 11 - 575 KB

Includes

- Chapter Eleven: Develop a support network. Look to family, friends, and teachers.

- Mentor Tip: Teen Support

- Mentor Tip: Supportive Environment

- Mentor Tip: Self-Determination Support

- Mentor Tip: Teen Relationships with Adults

- E-Community Activity: Developing Relationships with Adults

- E-Community Activity: Working with Adults

- E-Community Activity: Participating in Activities

- E-Community Activity: Being a Good Friend

- Mentor Tip: Friendships

- E-Community Activity: Developing Friendships

- E-Community Activity: Locating a Career OneStop

- E-Community Activity: Finding Resources and Support

Chapter 12- 357 KB

Includes

- PART III: WHERE TO GO FROM HERE

- Chapter Twelve: Share your story.

- E-Community Activity: Share Your Views on Success

- E-Community Activity: Share Your Views on Goals

- E-Community Activity: Share Your Views on Abilities

- E-Community Activity: Share Your Views on Strategies

- E-Community Activity: Share Your Views on Technology

- E-Community Activity: Share Your Views on Working Hard

- E-Community Activity: Share Your Views on Support Network

Chapter 13- 460 KB

Includes

- Chapter Thirteen: Sample Documents

- Sample Mentor Guidelines

- Sample Protégé Guidelines

- Sample Mentor Application

- Sample Parent/Guardian Consent

Chapter 14 - 474 KB

Includes

- Chapter Fourteen: Resources and Bibliography

- Electronic Resources

- Bibliography

Index- 150 KB

© 2006 University of Washington

Permission is granted to copy these materials for noncommercial purposes provided the source is acknowledged.

This book was developed with funding from The Mitsubishi Electric America Foundation and the National Science Foundation (cooperative agreement #HRD-0227995). However, the contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the funding sources, and you should not assume their endorsement.

Preface

Opportunity is missed by most people because it is dressed in overalls and looks like work.

— Thomas A. Edison —

We all have defining moments in our lives. However, much of our development comes through small, incremental steps in which friends, parents, teachers, and counselors play roles. As mentors, caring adults may have established long-term relationships with us and promoted our success. Many seemingly inconsequential interactions shaped who we are now and who we will become.

Although most of this networking develops informally, supportive relationships can be intentionally promoted. This book tells how to create and sustain an electronic community designed to support teens with disabilities. Strategies and content can be easily adapted to other populations.

The personal stories, mentoring tips, and activities for teens with disabilities included in this book can be used in an online mentoring community (also called an electronic mentoring community or e-mentoring community) to promote success in school, careers, and other life experiences. It includes steps that lead to a happy, healthy, successful future for anyone, regardless of the presence of a disability. In the community of young people and mentors described in this book, key questions are asked, but simple answers are not provided. It is a place where everyone can find opinions that reflect their own as well as alternative views. Online discussions help participants more fully understand themselves, as well as individuals and systems with whom they interact, as they chart their own course to success.

The set of strategies presented in this book has its foundation in the large body of research and practice in the areas of:

- success

- self-determination

- transition

- mentoring

- peer support

- community building

- electronic communication

We know too well that postsecondary academic, career, and independent living outcomes for people with disabilities are discouraging. We often hear about the problems young people with disabilities face—physical obstacles, social rejection, academic failure, unemployment, drug abuse, and medical crises. Much research focuses on identifying these problems and then developing specific strategies for overcoming them. This approach is consistent with research and practice regarding adolescents from other high-risk groups, which concentrate on helping youth avoid identified problems—pregnancy, drug abuse, high school dropout, criminal activity, academic failure, gang membership—or deal with these problems once they exist. In contrast, this book presents strategies that contribute to the overall positive development of youth, which will also help them avoid many types of problems in the future, as well as successfully deal with those they ultimately face.

After all, some people do overcome significant challenges and lead successful lives. What does success mean to them, and how do they achieve it? What internal characteristics do these individuals possess, and what external factors have been present in their lives? What advice do they have for helping young people build personal strengths to overcome the challenges they face now, as well as those they no doubt will face in the future? How can these individuals with relevant insights be brought together with young people with disabilities as they travel the road to adulthood? How can long-term relationships with mentors and peers help young people develop into competent, contributing, and content adults? How can successful strategies be applied in an online forum?

Overview of this Book

This book and the complementary video series, Taking Charge: Stories of Success and Self-Determination, explore positive internal characteristics and external factors that contribute to success—personally, socially, spiritually, academically, and professionally. These factors can be used to provoke thought and promote interaction between teens and caring adults.

The book also tells how you can set up a mentoring community on the Internet where young people and their mentors share ideas that contribute to a successful transition to adult life. A complementary video for this book, Opening Doors: Mentoring on the Internet, shares reports from teens and mentors who have participated in a successful e-mentoring community sponsored by DO-IT (Disabilities, Opportunities, Internetworking and Technology). Another video, How DO-IT Does It, shares details about the DO-IT Scholars program, within which this mentoring community is one strategy to help teens with disabilities achieve success in postsecondary education and careers.

Another complementary video, DO-IT Pals: An Internet Community, tells teens how to gain maximum benefit from and have fun in an electronic mentoring community. It also invites teens with disabilities to join the DO-IT Pals online community.

If you wish to set up your own electronic mentoring community, follow the instructions provided in Part I of this book and then choose online activities from Part II that are most appropriate for your participants. The discussion exercises described are targeted to college-bound teens with disabilities—high school students for whom a technical college, community college, or four-year institution is part of their future plans. However, activities can be easily modified for teens without disabilities, individuals at other age levels, and young people with different goals. For students whose reading level is low, speech output software can be used to read the messages aloud, or the student can work with an assistant side by side. The content of this book can also be used to stimulate in-person conversations and activities within your home, community group, summer camp, or classroom.

In this book you will not find the stories of movie stars, international leaders, or other celebrities. Although the content is based on personal experiences of successful people with disabilities, all of the people represented here would not be considered superachievers in all areas of their lives. You'll hear the stories of everyday people striving for the best life has to offer. This book highlights advice from people who confront barriers as challenges rather than deterrents, who find insight and humor during trying times. It shares some of the attitudes, skills, and strategies that have contributed to the success of people with a wide range of disabilities, abilities, experiences, and personalities. The experts who provide the major content for this book share their dreams, goals, challenges, successes, and frustrations. They tell about their experiences and give advice about how to successfully transition from high school to college, careers, and independent living. Perhaps their stories will provide inspiration as you help those around you define and achieve success for themselves.

In short, this publication is:

- a how-to book for setting up an electronic mentoring community

- an invitation to recruit teens with disabilities to the DO-IT Pals online program

- a collection of activities to help teens with disabilities develop self-determination skills and transition to college, careers, and independent living

- a place where you will gain insights from successful individuals who have met and continue to meet life's challenges, including those imposed by disabilities

The following video presentations complement the content of this book:

- Taking Charge 1: Three Stories of Success and Self-Determination

- Taking Charge 2: Two Stories of Success and Self-Determination

- Taking Charge 3: Five Stories of Success and Self-Determination

- Opening Doors: Mentoring on the Internet

- How DO-IT Does It

- DO-IT Pals: An Internet Community

These presentations can be freely viewed online on the DO-IT Video page or purchased from DO-IT in DVD format.

History and Current Trends Regarding People with Disabilities

For much of the content of this book, experts—people with disabilities who have been successful in academic studies and/or careers—were consulted. There are few publications like this in which the voices of people with disabilities are heard. Why is this the case? At least a partial answer lies in the history of isolation, exclusion, and dependence of people with disabilities (Fleischer & Zames, 2001).

Exclusion and Dependence

In early times, children born with disabilities were hidden and sometimes even killed. Feelings of shame and guilt were often associated with giving birth to a child with a disability. Sometimes the disability was blamed on sins of family members. Even as people with disabilities became more accepted, society viewed disability as a personal tragedy with which the individual and family must cope. Feelings of pity and actions of charity were typically evoked in others. Even successful individuals such as Franklin D. Roosevelt tried to hide their disabilities. Early on, organizations focused on the prevention and cure of disabilities. Successful funding campaigns, even to this day, often share images of helpless children with disabilities apparently doomed to a miserable life. In the 40s and 50s parents organized and advocated for education and services for their children with disabilities, but the children were not routinely encouraged to advocate for themselves. Children with disabilities rarely encountered successful adults with disabilities.

Civil Rights and Accommodations

The impact of the return of disabled veterans after World War II and the fights for civil rights of women and racial and ethnic minorities contributed to changing perspectives on disability in the United States. Growing numbers of people with disabilities and their advocates saw that it was not disability but rather an inaccessible environment and the negative attitudes of others that were the greatest contributors to the restrictions they encountered. Their view that access to programs and services was a civil right led to legislation that included the Architectural Barriers Act of 1968, the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the Education of All Handicapped Children Act of 1975 (later updated and renamed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, IDEA), and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA). These and other laws mandate that people with disabilities have full access to education, transportation, technology, employment, and other life experiences. Sometimes this requires that reasonable accommodations be made.

Universal Design and Diversity

Although buildings are now built with accessibility features as part of the original design, only recently has the concept of universal design been promoted in the development of technology, learning environments, services, work sites, and information resources (Burgstahler, 2001b). When universal design principles are applied, environments, programs, and resources are accessible to people with a broad range of abilities, disabilities, and other characteristics, minimizing the need for special accommodations. Widespread applications of universal design can ultimately lead to a world that is more accessible to everyone. They support the full inclusion of people with disabilities and other underrepresented groups in recognition that diversity is a necessary condition for excellence in education, employment, and social settings.

Self-Determination and Independence

The content of this book is supported by decades of research and scholarship that tell us about how individuals with different types of disabilities lead challenging and rewarding lives. Simply put, this book is about self-determination. But what is self-determination? There are many definitions from which to choose. The following definition (Field, Martin, Miller, Ward, & Wehmeyer, 1998, 1999) provides a foundation for the content of activities in this book.

Self-determination is a combination of skills, knowledge, and beliefs that enable a person to engage in goal-directed, self-regulated, autonomous behavior. An understanding of one's strengths and limitations together with a belief in oneself as capable and effective are essential to self-determination. When acting on the basis of these skills and attitudes, individuals have greater ability to take control of their lives and assume the role of successful adults. (Field et al., 1998, p. 2)

The Council for Exceptional Children (CEC), along with many other professional organizations and parent groups, embraces instruction in self-determination as a way to improve academic and career outcomes for youth with disabilities. Self-determination is also promoted in legislative mandates. For example, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act requires that students with disabilities actively participate in their transition planning and that their preferences and interests be considered. It affirms the right of people with disabilities to self-determination.

Gaining control over one's life involves learning and applying self-determination skills. These include self-awareness, goal-setting, problem-solving, and self-advocacy. The personal process of learning, applying, and evaluating these skills in a variety of settings is at the heart of self-determined behavior that leads to successful transitions to adulthood. The activities in this book provide opportunities for young people to reflect on their own experiences as well as learn and practice self-determination skills. They share the lessons learned by those who are successfully traveling the road to self-determined lives and provide a model of how young people can be guided toward self-determined behavior within an online mentoring community. Although not a comprehensive course on self-determination, the activities in this book are consistent with the performance-based standards for the preparation of special educators adopted by the National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education (2002) for program accreditation. Examples of characteristics of special education teachers that directly address components of self-determined behavior noted in this report include:

- "enhance the learning of critical thinking, problem solving,...." (p. 2)

- "increase their self-awareness, self-management, self-control, self-reliance, and self-esteem." (p. 2)

- "emphasize the development, maintenance, and generalization of knowledge and skills across environments, settings, and the lifespan." (p. 3)

- "foster....positive social interactions, and active engagement,...." (p.3)

- "encourage the independence, self-motivation, self-direction, personal empowerment, and self-advocacy...."(p.3)

- "develop a variety of individualized transition plans, such as transition from preschool to elementary school and from secondary settings to a variety of postsecondary and learning contexts." (p. 4)

- "use collaboration to facilitate the successful transitions...." (p. 6)

Growing evidence suggests that enhanced self-determination skills enable students with disabilities to perform more effectively in academic studies and thus support the goals of No Child Left Behind legislation and standards-based school reform. In addition, many state standards for students include elements of self-determined behavior such as goal setting, problem solving, and decision making. There exists a wide variety of self-determination curricula; some can be located by consulting the resources and bibliography in Chapter Fourteen of this book. The activities in this book were developed after a comprehensive literature review, with special attention given to the self-determination curriculum that has been field-tested (Test, Karvonen, Wood, Browder, & Algozzine, 2000).

Developing self-determination skills within an online mentoring community has limitations. It is recommended that the activities in this book be augmented with opportunities to apply what is learned. Teachers, parents, and other caring adults can help young people by providing opportunities for choice, problem solving, and decision making. For very young children, letting them choose between several books to read, games to play, or clothes to wear may be appropriate; as they grow older, opportunities for greater control should be provided. The key is steady growth in the number and complexity of choices they can make that affect their lives.

DO-IT

In 1992, with a grant from the National Science Foundation, I founded DO-IT at the University of Washington. DO-IT has grown from that seed into a collection of projects and programs that help young people with disabilities successfully pursue college and careers, using technology as an empowering tool. The disabilities of participants in DO-IT programs include sensory impairments, mobility impairments, attention deficits, and learning disabilities. DO-IT also helps educators, technology staff, librarians, and employers create academic offerings, information resources, and employment opportunities that are accessible to people with disabilities. (Burgstahler, 2006a, 2003a; Kim-Rupnow & Burgstahler, 2004).

My motivation to create DO-IT drew from both personal and professional experiences. My relationship with a family friend who was developmentally disabled taught me at a young age that no single set of criteria should be used to measure success. From my years as a middle and high school teacher I gained insight into the challenges teens face as they move toward adult life and the corresponding challenges caring adults face as they try to help them on this journey. Personal experiences with young people and adults with disabilities taught me that the low expectations and negative attitudes of others create the greatest barriers to success for people with disabilities and that facing the challenge of a disability is too often an isolating experience. My close relationship with a child who is quadriplegic revealed the doors that can be opened with assistive technology, telecommunications, and alternative strategies for reaching goals. My roles as an aunt and as a mother created my greatest interest in exploring how we can help children define success for themselves and develop the beliefs, attitudes, and skills they need to set and reach these goals.

DO-IT is a collection of projects and programs to increase the number of people with disabilities who:

- use technology as an empowering tool

- communicate with peers and mentors in a supportive electronic community

- develop self-determination skills

- succeed in postsecondary education and employment

- pursue careers that were once considered unavailable to them, such as science and engineering

- have opportunities to participate and contribute in all aspects of life

Life Stages of DO-IT Participants

| Level | Participants |

| High School | DO-IT Scholars DO-IT Pals |

| College | DO-IT Ambassadors DO-IT Mentors |

| Careers | DO-IT Ambassadors DO-IT Mentors |

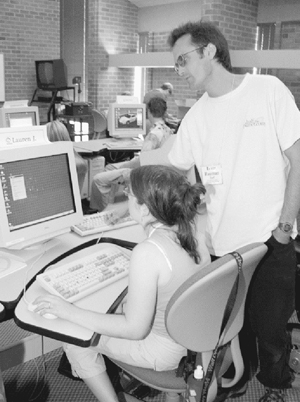

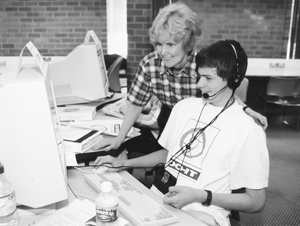

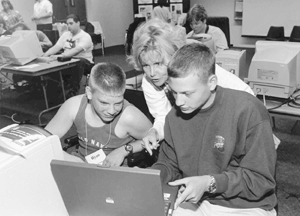

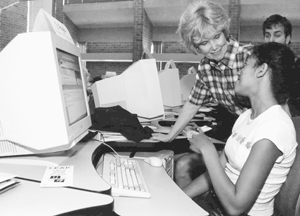

Most of the stories and advice presented in this book belong to DO-IT Scholars, Pals, Ambassadors, and Mentors. DO-IT Scholars are college-bound high school students with disabilities who are self-motivated, are successful in school, and show leadership potential. Their disabilities include mobility impairments, visual impairments, hearing impairments, learning disabilities, attention deficit disorders, speech impairments, and health impairments. Scholars attend at least two residential Summer Study programs at the University of Washington in Seattle. They are introduced to college life, resources, and academic studies and develop self-determination skills. They participate in internships and other work-based learning experiences that prepare them for career success.

With computers and assistive technology, they use the Internet to access information and communicate with others in a stimulating electronic community. High school graduates who continue to participate as DO-IT Scholar alumni become DO-IT Ambassadors. As Ambassadors, they mentor younger Scholars and contribute to DO-IT efforts in many ways. The community also includes DO-IT Mentors—other college students, faculty, and professionals in a wide variety of fields, many of whom have disabilities themselves. DO-IT Pals, college-bound teens with disabilities from around the world who wish to participate in our online mentoring community, have joined the DO-IT family as well. The success of this approach where young people and adults share their views in a mentoring community motivated me to include the perspectives of a large group of people with disabilities in this book.

During the more than a dozen years I have initiated and directed DO-IT's successful electronic community, I have often been asked by other program directors how to design and support their participants through similar online interactions. It is easy to describe the basic scheme. But attention to myriad details and ongoing operations makes the system work. This book shares both the process and examples of the content of DO-IT's electronic community in a way that lessons learned can be applied in other circumstances and with different audiences. The fact that our participants have disabilities, for example, is just one characteristic of our target audience. The basic concepts and activities can be tailored to any group of teens, or, with some modifications, they can be used with younger students, with adults, or with students from other groups facing special challenges due to racial/ethnic background, gender, or socioeconomic status.

The Role of Technology in Creating this Book

Most of the personal stories, online activities for teens, and tips for mentors included in this book were collected over the Internet. To complete this work, I sent questions via electronic mail to DO-IT Scholars, Pals, Ambassadors, and Mentors and to some participants with disabilities in other programs funded by the Mitsubishi Electric America Foundation. Contributions were returned in email messages. Those who are blind used speech and Braille output systems to read my requests. Those with mobility impairments used specialized software and alternative keyboards to enter their contributions. For those who have difficulty communicating face to face because of speech or hearing impairments, their disabilities did not impact their participation in these Internet-based communications.

Responses to requests for input were numerous and lengthy. I edited the original messages to fit the material into a book of reasonable length. I attempted to capture the essence of each contribution.

What You'll Find in this Book

The chapters in this book take you on a journey of discovery, looking at success and self-determination from a variety of perspectives and learning how students with disabilities can be supported within an online mentoring community. The book is divided into three main sections.

PART I addresses the philosophy and purpose of online mentoring. It tells how to establish the community, recruit and train mentors and protégés, provide guidelines for participants, and initiate online discussions. Complementary videos reinforce this content.

PART II is organized around seven recommendations that were synthesized from hundreds of responses from the young people and adults with disabilities who contributed to the content (Burgstahler, 2006c):

- Define success for yourself.

- Set personal, academic, and career goals. Keep your expectations high.

- Understand your abilities and disabilities. Play to your strengths.

- Develop strategies to reach your goals.

- Use technology as an empowering tool.

- Work hard. Persevere. Be flexible.

- Develop a support network. Look to family, friends, and teachers.

Each chapter contains the text of messages to support an online community. Each can be sent by a program administrator to mentors alone or to mentors and protégés together.

PART III presents protégés and mentors with a forum to share their own stories and experiences and suggests additional resources for participants and administrators.

How to Use this Book

This book is designed for use by a parent, guardian, teacher, or program administrator searching for strategies to help young people with disabilities gain the skills they need to lead successful, self-determined lives. Specific guidelines are included for setting up and supporting a mentoring community on the Internet. If you do not have access to the Internet at home or school, explore Internet access options at your local library. Once the technical aspects of the community are dealt with and the participants identified, the electronic community administrator should choose mentoring tips and online activities that are appropriate for the people with whom they work. Although the online activities are presented in a logical order, they can be used in any order appropriate for the target audience.

Completing the activities presented in this book will help precollege students with disabilities identify their strengths and challenges and develop skills for success in all areas of their lives. If you are not in a position to create and support an electronic community, consider using the activities in a classroom, computer lab, summer program, or other setting, with or without computers. Activities can be completed independently but are more stimulating when a young person works with a fellow student, mentor, or other adult. In a group with their peers, even reluctant learners choose to participate. Sharing responses and ideas in a small group stimulates a rich discussion once participants realize there are no right answers and everyone's opinion has value.

How to Download or Purchase this Book and Complementary Videos

It might be helpful for you to have electronic copies of the exercises for modification and application in your setting. The most current electronic copy of these materials can be found at Creating an E-Mentoring Community: How DO-IT does it, and how you can do it too. Videos that complement the content of this book can also be found there for free online viewing; trainers can freely download copies of videos to project from their own computers by directing requests to doit@u.washington.edu. Other DO-IT videos can be viewed on the DO-IT Video page.

Copies of the printed book and videos can also be purchased from DO-IT. Details can be found on the DO-IT Free Publications Order Form. Free DO-IT publications can be found on the Resources page.

Sheryl Burgstahler, Ph.D.

Founder and Director, DO-IT

College of Engineering and Computer Science

Computing & Communications

College of Education

University of Washington

Part I: Creating an Electronic Mentoring Community

PART I of this book, comprising Chapters One through Four, addresses the philosophy and purpose of online mentoring. It tells how to design an electronic mentoring community, recruit and train participants, promote online discussion, and begin to explore the topics of success and self-determination.

The entire content of this book can be found at at the titular page of this book. Use this electronic version to cut, paste, and modify appropriate content for distribution to participants in your electronic community; please acknowledge the source.

Chapter One provides an introduction to the philosophy and purpose of online mentoring and explores its benefits to participants. Along with the complementary video, DO-IT Pals: An Internet Community, this chapter shares the model of the DO-IT online community.

Chapter Two explains a step-by-step process for setting up an online mentoring community where young people are supported by caring adults. A complementary video, Opening Doors: Mentoring on the Internet, reinforces basic mentoring concepts and methods and documents the value of online mentoring for both mentors and protégés. How DO-IT Does It provides the context in which an electronic mentoring community is employed as a strategy to promote the success of people with disabilities.

Chapter Three addresses orientation and training to help new mentors prepare for the unique challenges of online mentoring. It includes email messages for mentors, as well as guidelines to send to new protégés regarding communication and Internet safety.

In Chapter Four mentors and protégés begin to explore the topics of success and self-determination. Five stories of success and self-determination are presented in the video series Taking Charge: Stories of Success and Self-Determination. This chapter introduces the content explored in depth in PART II of the book.

Chapter One

An Introduction to E-mentoring and E-communities

No country, however rich, can afford the waste of its human resources.

— Franklin D. Roosevelt —

Individuals with disabilities experience far less career success than their peers who do not have disabilities; however, differences in achievement diminish significantly for those who participate in postsecondary education (Blackorby & Wagner, 1996; Stodden & Dowrick, 2000; Yelin & Katz, 1994). College graduates with disabilities achieve success in employment close to that achieved by those without disabilities. Although the rate of participation in higher education is lower for people with disabilities than it is for people without disabilities, this difference is diminishing (Henderson, 2001; National Council on Disability, 2000).

A bachelor's degree or higher is a prerequisite for many challenging careers, including high-tech fields in science, engineering, business, and technology. Few students with disabilities pursue postsecondary academic studies in these areas, and the attrition rate of those who do is high (National Science Foundation, 2000; Stodden & Dowrick, 2000).

Lack of job skills and related experiences also limit career options for people with disabilities (Colley & Jamieson, 1998; Unger, Wehman, Yasuda, Campbell, & Green, 2001). They also have little contact with other people with disabilities and, thus, limited access to positive role models with disabilities (Seymour & Hunter, 1998).

Low expectations of and lack of encouragement from those with whom they interact can impede the realization of the full potential of people with disabilities in challenging fields. Support systems in high school are no longer available after graduation, and many students with disabilities lack the self-determination, academic, and independent living skills necessary to make successful transitions to college and careers (National Information Center for Children and Youth with Disabilities, 1999).

Youth with disabilities more often continue to live with their parents or in other dependent living situations after high school than their peers without disabilities. They also engage in fewer social activities. The effect of social isolation can be far-reaching, affecting not only personal well-being but also academic and career success (Seymour & Hunter, 1998).

The lives of some people with disabilities demonstrate that they can overcome challenges imposed by inaccessible facilities, curriculum materials, equipment, and electronic resources; lack of encouragement; and inadequate academic preparation and support (American Association for the Advancement of Science, 2001; National Center for Educational Statistics, 2000; National Council on Disability and Social Security Administration, 2000). Steps to careers for students with disabilities include preparing for, transitioning to, and completing a college education; participating in relevant work experiences; and transitioning from an academic program to a career position.

Research studies have identified successful practices for bringing students from underrepresented groups into challenging fields of study and employment. They include the provision of:

- technology

- programs that bridge between academic levels and between school and work

- work-based learning opportunities

- peer support

- mentoring

In this chapter, strategies developed in DO-IT's award-winning online mentoring community are shared so that you can apply successful practices in your program.

Acknowledgement: Much of the content of this chapter is published in earlier work (Burgstahler, 1997, 2003b, 2006a; Burgstahler & Cronheim, 1999, 2001; DO-IT, 2005).

Peer, Near-Peer, and Mentor Support

Most of us can think of people in our lives who supplied information, offered advice, presented a challenge, initiated a friendship, or simply expressed an interest in our development as a person. Without their intervention we might have remained unaware of a resource, neglected to consider an exciting opportunity, progressed toward a goal at a slower pace, or given up on a goal altogether.

Supportive relationships with peers and adults can positively impact the transition period following high school when a student's structured environment ends and precollege support systems are no longer in place. Within social support systems, participants provide what has been defined as communication support behavior, "whereby individuals within a formal social system offer and receive information and support from one another in a one-way or reciprocal manner" (Hill, Bahniuk, Dobos, & Rouner, 1989, p. 356).

Mentor Support

The term mentor comes from Homer's Odyssey, in which a man named Mentor was assigned the task of educating the son of Odysseus. Protégé (or mentee) refers to the person who is the focus of the mentor's efforts. Mentoring has long been associated with a variety of activities including counseling, role modeling, job shadowing, advice-giving, and networking.

Young people with disabilities can be positively influenced by observing role models with similar disabilities successfully pursuing education and careers that they might otherwise have thought impossible for themselves. Mentors can help their protégés explore career options, set academic and career goals, examine different lifestyles, develop social and professional contacts, identify resources, strengthen interpersonal skills, achieve higher levels of autonomy, and develop a sense of identity and competence. Information, guidance, motivation, resources, and emotional support provided by mentors can help young people successfully transition from high school into the less structured environments of postsecondary education, employment, and community living.

Protégés report benefits of mentoring to include

- better attitudes toward school and the future,

- decreased likelihood of initiating drug or alcohol use,

- greater feelings of academic competence,

- improved academic performance, and

- more positive relationships with friends and family (Campbell-Whatley, 2001).

Protégés are not the only ones who benefit from mentoring relationships. Adults can also find satisfaction in their helping roles. Common positive effects for mentors include

- increased self-esteem,

- feeling of accomplishment,

- insights into childhood and adolescence, and

- personal gain, such as increased patience, a sense of effectiveness, and the acquisition of new skills or knowledge (Rhodes, Grossman, and Resch, 2000).

In summary, "mentoring is a win-win situation. Young people win, adult volunteers win. It is, quite frankly, society at large that is eventually the real winner" (Saito & Blyth, 1992, p. 60).

Group Mentoring

At least in part because of a shortage of available adult mentors, group mentoring programs have emerged. Typically, in this model one mentor is assigned to a small group of young people. In group mentoring, mentors cannot provide as much individual attention to each young person as they might in the traditional one-to-one model, but positive outcomes can also be achieved as a result of participant interactions. Although, as with one-to-one mentoring, most group mentors want to develop personal relationships with protégés, they also promote positive peer interactions. Participants report that group mentoring helps them improve social skills, relationships with individuals outside of the group, and, to a lesser extent, academic performance and attitudes (Herrera, Vang, & Gale, 2002; Sipe & Roder, 1999).

Peer and Near-Peer Support

Peers can offer some of the same benefits to young people as mentors. Like mentors, peers can coach and counsel, offer information and advice, provide encouragement, act as sounding boards, function as positive role models, and promote a sense of belonging. Peers of the same age offer unique opportunities for sharing, are easier for participants to approach than adult mentors, and typically develop relationships that are longer lasting than those established with adults. While mentoring relationships are primarily one-way helping relationships, peer relationships offer a higher degree of mutual assistance, with both individuals giving and receiving support. Peers facing similar challenges related to their disabilities can share strategies to overcome disability-related barriers.

Relationships with individuals who are a year or two older than protégés, sometimes called near-peers, offer a powerful combination of the benefits of peer and mentor relationships. Near-peers and protégés can discuss issues such as whom on campus to tell about a disability, how to communicate with professors about accommodations, how to live independently, and how to make friends. In addition, near-peers can become empowered as they come to see themselves as contributors and role models.

Computer-Mediated Communication

Mentor, peer, and near-peer relationships have the potential to provide students with disabilities with psychosocial, academic, and career support, thereby lessening or eliminating some of the unique challenges they face. However, these types of relationships can be limited by physical distance, time, and schedule constraints and, in some cases, disability-related communication barriers (e.g., speech impairments, deafness).

For these relationships to be successful, it is often necessary to match young people and mentors who are in close geographic locations. Even if such relationships can be established, communication, transportation, and scheduling problems must be resolved. In short, arranging traditional in-person mentoring and peer support for this population is problematic.

Computer-mediated communication (CMC), wherein people use computers and networks to communicate with one another, makes communication across great distances and different time zones convenient, eliminating the time and geographic constraints of in-person communication. CMC facilitates the development of communities for people with common interests, regardless of their physical locations. Using electronic mail, text messaging, chat rooms, web-based forums, and other technology to sustain meaningful relationships between people who are geographically disconnected allows us to reconsider the concept of community as a physical location. The lack of social cues and social distinctions like gender, age, disability, race, and physical appearance in CMC can make even shy participants willing to share their views.

The development of computers and assistive technology makes electronic communication possible for all individuals, regardless of disability. For example, a person who is blind or has a disability that makes reading difficult can use text-to-speech software to read aloud text presented on a computer screen. An individual with limited use of his hands can use a trackball, a headstick, speech input, or an alternative keyboard to control the computer; and a person with a speech or hearing impairment may be able to participate more fully in communications when they are conducted electronically.

E-Mentoring Communities

Online discussion groups, chat rooms, web-based forums, and other CMC vehicles have emerged as popular tools for interaction between individuals within groups. When CMC is the mode for communication between mentors and their protégés, it has been called e-mentoring, online mentoring, or telementoring. As in traditional on-site mentoring, the mentor, often an adult, develops a close relationship with a younger person in order to promote his or her well-being and success.

One advantage of an online mentoring community (or electronic mentoring community, or e-community), as compared to more traditional one-to-one electronic mentoring, is that mentors observe the communications of other mentors as well as the responses of all of the young people in the community. In this format, once basic guidelines are provided, mentors learn effective mentoring techniques on the job. They can also more effectively and efficiently share their expertise and insights, since no individual is responsible for providing all mentoring communications with a specific protégé in the community. With this approach, each participant benefits from the expertise of a group of mentors, peers, and near-peers.

DO-IT's E-Mentoring Community

In DO-IT programs, mentor, peer, and near-peer support sometimes occurs in person, but most of the time is delivered through its e-mentoring community. Participants are mentored within a group, and many contributors are included in interactions. Participants also disseminate academic and career-enhancing resources that benefit all community members. Positive aspects of DO-IT's e-community approach include the following:

- Individuals benefit from the experiences of a large group of mentors, peers, and near-peers.

- Mentors can specialize in the areas of their strongest expertise.

- The program performs successfully even though some mentors are less available and skilled than others.

- Using asynchronous, text-based communication on the Internet eliminates barriers faced by other forms of communication that are imposed by location, schedule, and disability.