Making K-12 Computer Science Accessible (2017)

March 8, 2017

Seattle, WA

Proceedings of the March 2017 AccessCSForAll Capacity Building Institute (CBI)

This publication shares the proceedings of a CBI entitled Making K-12 Computer Science Accessible. The content may be useful for people who:

- participated in the CBI,

- teach Exploring Computer Science (ECS), Computer Science Principles (CSP), or another K-12 computing course,

- train teachers of K-12 computing courses,

- seek to increase their understanding of issues surrounding the participation of students with disabilities in computing education and computing careers,

- would like to access resources to help make their courses, services, and activities more welcoming and accessible to students with disabilities, or

- have promising practices to share with others.

About AccessCSForAll

AccessCSForAll: Including Students with Disabilities in Computing Education for the Twenty-First Century (AccessCSForAll) works to increase the successful participation of students with disabilities in K-12 computing courses. Central to this work is partnerships with other projects funded by the Computing Education for the 21st Century program of the National Science Foundation (NSF) Directorate for Computer and Information Science and Engineering (CISE) and other organizations that train computer science teachers and develop curricula for ECS and CSP. AccessCSForAll is led by the Department of Computer Science and Engineering and the DO-IT (Disabilities, Opportunities, Internetworking, and Technology) Center at the University of Washington (UW) and the Department of Computer Science at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. It is funded by CISE (Grant #CNS-1440843 and #CNS-1440878).

AccessCSForAll focuses on the inclusion of students with disabilities in these courses through two objectives:

- building the capacity of K-12 computing teachers to serve those students through professional development for trainers who provide professional development to teachers, curricular units, online tutorials, virtual communities of practice for teachers, and real-time, individual teacher support; and

- creating accessible materials, both tools (including iterative refinement and deployment of the Quorum language) and curricular units, that K-12 computing teachers and students can use in their classrooms.

The ultimate goal of AccessCSForAll is to increase the participation of people with disabilities in computing academic studies and careers and to enhance those fields with their unique perspective and expertise.

About the CBI

The Making K-12 Computer Science Accessible CBI, sponsored by AccessCSForAll, was held in Seattle, WA on March 8, 2017, as a pre-symposium workshop of the annual Association for Computing Machinery's (ACM) Special Interest Group on Computer Science Education (SIGCSE) Technical Symposium. Its purpose was to encourage and support efforts to make K-12 courses more welcoming and accessible to students with disabilities. Attendees included postsecondary faculty, individuals who provide professional development for K-12 teachers, secondary teachers, disability services professionals, and individuals with disabilities.

As is typical of a CBI

- All participants contributed to its success.

- Speakers participated in group discussions.

- Experts in all topic areas were in the audience.

- Participants gave presentations and participated in large and small group discussions.

- Some predetermined professional development was presented and new content was delivered as the meeting unfolded.

- Participant interests were expressed and expertise was made known.

The CBI provided a forum for discussing recruitment and access challenges, sharing successful practices, developing collaborations, and identifying systemic change initiatives for increasing the participation of students with disabilities in ECS and CSP courses.

Topics discussed included

- universal design of instruction (UDI) and academic accommodations;

- accessibility of programming environments;

- technology and accessible IT design;

- alternative non-visual development projects for students with disabilities; and

- best practices for making courses welcoming and accessible to students with disabilities.

The agenda for the CBI, summaries of the presentations, and working group discussions are provided on the following pages.

CBI Agenda

Wednesday, March 8

8:30 AM

Introductions & Breakfast

9:00 AM

Presentation: Including Everyone in CS for All

Richard Ladner, University of Washington & Andreas Stefik, University of Nevada Las Vegas

Video: How Can We Include Students with Disabilities in Computing Courses?

9:45 AM

Presentations: Accessibility of Programming Tools

- Accessible Blockly Library – Cory Diers, Google

- Blocks4All: Making Block Languages Accessible Using a Touchscreen – Lauren Milne, University of Washington

- Tangibles + Audio Stories = Programming + Fun – Varsha Koushik, University of Colorado Boulder

- Accessibility in Bootstrap – Kathi Fisler, Worcester Polytechnic Institute & Bootstrap

11:00 AM

Presentations: Accessibility of Curriculum

- Universal Design of Learning via Panopto – John Dougherty, Haverford College

- Students with Cognitive Disabilities – Maya Israel, University of Illinois

- Multisensory CS Instruction to Provide Access to Students with Invisible Disabilities – Meg Ray, Cornell Tech

- Accessible CSP for Students with Learning and Attention-Based Disorders – Sarah Wille, University of Chicago

- Dyslexic Children Programming: Overcoming Barriers Through Better Interaction– Rob Thompson, University of Washington

12:30 PM

Lunch

1:30 PM

Discussion: Strategies for Improving Accessibility

2:15 PM

Divide into Working Groups

3:00 PM

Working Groups: What Can You Do to Improve Accessibility of Your Materials?

4:15 PM

Report-outs From Working Groups

4:45 PM

Evaluation & Wrap Up

Presentation Summaries

Accessible Blockly: Making a Visual Coding Environment Accessible

By Cory Diers, Kevin Chao, and Yi-Yi Kung

Blockly is a library for creating visual programming editors. It’s easy to use because a student doesn’t have to know syntax in order to program, and Scratch and Code.org are promoting it. We want to make Blockly Games accessible to blind students. A lot of kid-facing user experience (UX) relies on visual metaphors to restructure forms of knowledge. How might we make a highly visual UX design, like the one in Blockly, accessible to those who are visually impaired?

This presents a variety of design challenges:

- We chose to develop a separate accessible web version because of the following:

- Blockly uses lots of java script; it’s not your usual mostly-HTML webpage.

- The heavily-visual puzzle-block user interface (UI) doesn’t necessarily translate well to blind users.

- Existing games don’t really make sense non-visually.

Accessible Blockly can be used to make a music game. It utilizes HTML to translate Blockly’s stacks of blocks into a nested table view that can be easily walked by a screen reader. We found a challenge was getting used to the UI and how to do simple operations. So, we built some tutorial levels to introduce users to the basics of manipulating blocks, and a main game with levels that build on each other to produce the entire tune to Frere Jacques. Along the way, they learn sequential execution and for loops.

Still, there are multiple UI challenges, including the following:

- Moving blocks from toolbox to workspace

- Instructions need to be clear but non-verbose

- In the workspace, one island or multiple islands?

- Orientation: how do students know “where they are”?

We did some UX research with students from the California School for the Blind. We found that kids weren’t as familiar with using screen readers than we expected them to be. The auditory music component of the game was very useful for kids who used the auditory feedback to hear if they had correctly written their program. Kids struggled with navigating the tree structure of the interface. Kids had trouble understanding the relationship between the components of the interface, particularly the toolbox-workspace relationship.

We took this feedback into account, and iterated on the design. Out next iteration will introduce screen reader functionality before jumping into Blockly proper. We suspect this will make it easier to jump into navigating “full” Blockly. We also had problems with the three-column design, and opted for a two-column design, where the “toolbox” is now its own dialog under the menu. Navigation is easier in this system, since it’s harder to accidentally find yourself switching from workspace to toolbox and back. We also decided to replace the “copy-paste” metaphor with linking. “Marking a spot” and placing a block there proved to be a more intuitive UI for our users in our second test.

Blocks4All: Making block languages accessible using a touchscreen

By Lauren Milne

Block programming environments such as Scratch and Blockly, are popular educational tools to teach children how to program, as they allow children to avoid learning syntax and focus instead on logic and common programming concepts. However, current block programming environments rely heavily on visual aspects: the blocks are pieces of code that act like puzzle pieces that fit together only if the code is syntactically correct. These visual aspects are inaccessible to blind children, so these children are being left behind their peers in access to computer science education. We are exploring to make these types of programs accessible to blind children using a touchscreen tablet and have developed a prototype.

Tangibles + Audio stories = Programming + Fun

By Varsha Koushik

Visual block programming languages like Scratch, Blockly, and Snap are a popular way of introducing kids to programming. However, a visual programming environment with graphical presentations for blocks, program creation, and program execution is inaccessible to visually impaired users.

Can programming become more accessible to visually impaired users?

Non-visual programming research has gained momentum in the recent past. Quorum [1] is an evidence-based programming language that is used by both sighted and non-sighted users. BraillePlay [2] explores the use of touch screens for block languages. Pseudo Blocks [3] is a pseudo spatial blocks language that uses keyboard navigation and synthetic speech to create programs. Screen-based approaches require proficient screen reader knowledge and majority of visually impaired kids are novice users. Block shapes still remain a constraint for visually-impaired users to learn block languages.

Can tangibles indicate shapes more intuitively?

Osmo system [4], Project Bloks [5], and Project Torino [6] use iPad, pucks, and baseboards to create programs and electronic components. Of these approaches, Project Torino explores sighted and non-sighted user collaboration. Compelling audio feedback remains a limitation to these approaches. Stories are often used as a learning tool for visually impaired kids. Alice [7] and StoryTelling Alice [8] have used stories to teach programming using a 3D visual environment.

Can a tangibles and audio stories be used to teach programming?

Our system uses a set of characters with interesting sound effects and voice outputs. We have designed physical pieces that are intuitively identifiable, convey program flow, and follow features of blocks language. Programs are sequential with each line of the program being a combination of nouns and verbs. A base with distinctively shaped sockets are used for program creation. Audio feedback and associated sound effect is provided for each interaction in the program. Unique reactivion tags are attached to each piece and computer vision is used to track interactions in real time. Using this system we want to teach programming concepts like loops, conditions, program flow and subroutines. This system will be part of group classroom activities along with structured activities. In the future, we envision this system to be used a scaffolding tool for advanced programming languages. We also want to include braille to encourage braille literacy and provide features to share work online. We also want to integrate this system into other domains like math, science, and music.

Questions we are looking to get feedback on are listed below:

- How to forefront programming concepts?

- How can this be used as a scaffolding tool for advanced programming?

- Ideas for activities using this tool?

- How can it be tied to other domains?

- How to evaluate with end users or teachers? How can we get teachers excited about this?

References

- Stefik, A., & Siebert, S. (2013). An empirical investigation into programming language syntax.ACM Transactions on Computing Education, 13(4), 19.

- Milne, L. R., Bennett, C. L., Ladner, R. E., & Azenkot, S. (2014, October). BraillePlay: educational smartphone games for blind children. In Proceedings of the 16th International ACM SIGACCESS conference on Computers and Accessibility (pp. 137-144).

- Koushik, V., & Lewis, C. (2016, October). An Accessible Blocks Language: Work in Progress. In Proceedings of the 18th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility (pp. 317-318).

- Horn, M. (n.d.) Osmo System. Available here.

- Google. (n.d.) Project Bloks. Available here.

- Morrison, C. (n.d.) Project Torino. Available here.

- Pausch. (n.d.) Alice. Available here.

- Kelleher. (n.d.) StoryTelling Alice. Available here.

Supporting Visually-Impaired Programmers through Bootstrap

By Kathi Fisler, Bootstrap

The Bootstrap team has been working to make our programming tools work effectively with screen readers. This presentation describes our progress and some of the underlying techniques that we’ve used.

Unlike many curricula, Bootstrap programs produce a variety of rich outputs, including video games, physics simulations, reactive applications, images, and tabular data. We link these to screen readers using data annotations that present the structure of a constructed output. To build these annotations, we modify the runtime system of our programming language. Controlling the language runtime (since we implement our entire language stack) has greatly simplified the task of providing rich structural descriptions of outputs.

We are also developing techniques to help people use audio to structurally navigate code, including programs that fail to parse due to syntax errors. Rather than read code symbol by symbol, we annotate code with structural summaries that users can expand as appropriate. The syntax of our programming language allows us to create structural summaries and handle code with syntax errors more easily than in many other programming languages.

More details are available on the Bootstrap blog at www.bootstrapworld.org/blog/index.shtml.

UDL with Panopto

By John P. Dougherty

Universal design in learning (UDL) promotes the design and usage of flexible, often complementary, environments that accommodate individual student differences in learning [2]. Panopto is a software tool for lecture capture that provides a recorded live presentation synchronized with computer projection. We demonstrate how Panopto, in conjunction with a learning management system (LMS) such as Moodle, provides a temporally disconnected means for students to re-engage with classroom meetings that may not be completely or effectively accessed in real-time. Features of this approach include portability (i.e., the instructor needs only a web camera with microphone mounted on a tripod pointing at the board), along with easy to use by both instructors and students. We find the system is inexpensive, assuming your institution already has an LMS and access to Panopto, as well as in class projection and Internet. Once “debugged,” the system is also quick to use.

We spend time at the start of (and periodically throughout) the course emphasizing the role and responsibility of learning for all students, including those who may need accommodation of any kind. We then introduce lecture capture as a means to provide an alternative way to view the course material that should supplement (i.e., not replace) course meetings. We were initially uncomfortable with such raw presentations made permanent as there was no explicit time set aside (or available) to rehearse, but it became necessary to get over this fear and embrace the chaos, if only so students will see that struggle is often needed for mastery learning [1].

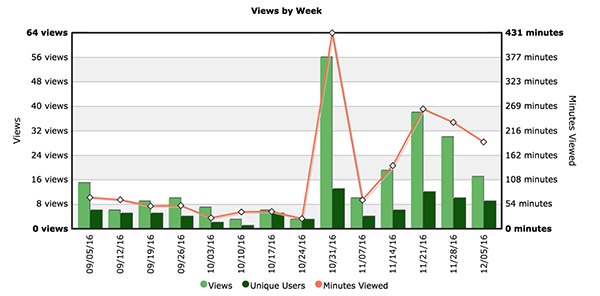

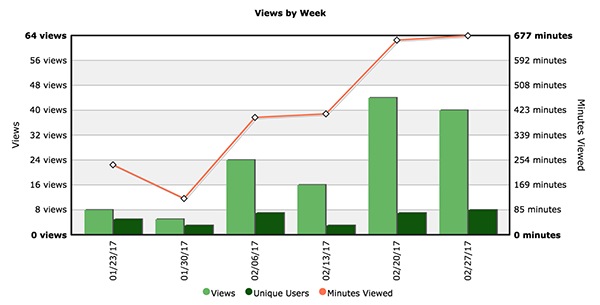

Preliminary results suggest that although the captured lectures are available to everyone enrolled in the course, only a small percentage (~22 %) use the system consistently. As expected, usage increases closer to the midterm examination time in Figure 1, as well as a midterm examination towards the end of Figure 2 (which only covers the first part of a course in progress). Survey responses indicate that the captured lectures are seen as having a positive impact on students’ perceived learning.

In conclusion, we offer this approach as satisfying the goals of UDL by providing another means to review materials that is available to everyone with the hope of supporting whomever needs this type of access. We do not present Panopto as a UDL panacea, but more as a simple and potentially effective way to increase course access. We also recommend the following for instructors:

- Commit: For each class, get there early and end a bit early.

- Prepare students: Explain why you are capturing the lecture.

- Prepare for lecture: Slides will help guide lecture, and can be made available to students prior to the course meeting; one might even prepare interactions (e.g., program development and execution).

- Get over shyness: If people can watch you in person, then it is fine on video.

References

- Ames, C. & Archer, J. (1988). Achievement goals in the classroom: Students’ learning strategies and motivation processes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(3), p.260.

- Rose, D. H., Meyer, A., Strangman, N., & Rappolt, G. (2002). Teaching every student in the digital age: Universal design for learning. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Students with Cognitive Disabilities and CS Education

By Maya Israel

Both student-specific challenges and instructional challenges make computing challenging for students with cognitive disabilities (learning disabilities and autism spectrum disorders). We are taking steps towards addressing these challenges.

Learning disability (LD) is a difference in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understanding or in using language, spoken or written, that may manifest itself in a limited ability to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell, or to do mathematical calculations, including conditions such as perceptual disabilities, brain injury, minimal brain dysfunction, dyslexia, and developmental aphasia. Students may have specific learning disabilities in oral expression, listening comprehension, written expression, basic reading skills, reading comprehension, mathematics calculation, or mathematics reasoning.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a developmental disability significantly affecting verbal and nonverbal communication and social interaction. It is generally evident before age three and may adversely affects a child’s educational performance. Other characteristics include engagement in repetitive activities and stereotyped movements, resistance to environmental change or change in daily routines, and unusual responses to sensory experiences.

Instructional challenges for teaching computing to this population include the following:

- Students with disabilities often miss part or all of computer science classes for various reasons.

- Paraeducators and instructional aids have little or no background in the subject, do not have access to lesson plans, and receive little guidance on how to help with computer science instruction.

- Computer science teachers may not understand disabilities or accommodation, have an entire class of students to teach, and may not be familiar with pedagogical approaches that are helpful to students with disabilities.

- Between instructional challenges (inaccessible curricula, low expectations, and a lack of strategies) and computing-specific challenges (ill-defined problems, multi-step complex problems, and open exploration), many students with disabilities are being set up for failure.

- There needs to be communication regarding curriculum and student needs that include the CS teacher, paraeducators, and special educators.

Suggestions for Instructional Aides/Paraeducators

- Environmental Considerations: Placement Matters

- If possible, students with disabilities should be seated alongside peers rather than segregated together in the back of the class. This sets the stage for peer collaboration.

- Professional Knowledge:

- Ask the computer science teacher to see lesson plan ahead of time if possible.

- Clarify the big ideas of the lesson.

- Communicate with the special ed teacher about about how accommodations and supports from other content areas (e.g., math and science)

Suggestions for computer science teachers

- Build a culture of collaboration

- Think about structured collaboration

- Consider using universal design for learning to build flexibility in how content is taught and how students demonstrate understanding

- Communicate with the special educators about what works in other content areas

- What strategies work during math and science?

- What accommodations are provided

- How can the paraeducator/aide best be used to support the student?

For more information, visit the University of Illinois' Creative Technology Research Lab website.

Multi-sensory Computer Science Instruction to Provide Access to Students with Invisible Disabilities

By Meg Ray

Across the K-12 spectrum and in every classroom setting, whether it’s special education, a mainstream classroom, a gifted and talented program, or a program for English language learners, it’s likely that you’ll have students with invisible disabilities. There are a range of invisible disabilities including emotional and behavioral disorders, learning disabilities, attention deficits, autism spectrum disorders, mild cognitive impairments, mild developmental delays, processing disorders, and speech and language impairments. Utilizing a variety of pedagogical frameworks including multi-sensory instruction, universal design of learning, K-12 CS frameworks and standards, and positive behavioral interventions and supports can help to support these students.

Strategies to consider vary depending on grade level:

- For Kindergarten through second grade

- Singing

- Skits & role playing

- Figures or pictures of bugs

- Tangible connections

- For third grade through fifth grade

- Programming movement

- Multiple types of code

- Block code images and manipulation

- Concrete to abstract

- For sixth through eighth grade

- “Traditional” and digital making

- Connect programs to the physical world

- Multi-language platforms

- Program visual and oral reports

- For ninth through twelfth grade

- Markup/Syntax cubes

- Human markup/syntax

- “Tagging” the classroom

- Accessible cheatsheets, card decks, anchor charts

- Interdisciplinary projects

- Use for markup or syntactic programming languages

Accessible Computer Science Principles for Students with Learning and Attention Deficit-Based Disorders

By Sarah Wille, Outlier Research & Evaluation at the University of Chicago

A 2014 publication entitled “The State of Learning Disabilities,” reports there are 2.4 million public school students in the U.S. identified with a specific learning disability (such as in reading, written expression, math, or language) and 6.4 million children diagnosed with an attention deficit disorder (like attention deficit hyperactivity disorder). This report indicated that as many as one-third of the 2.4 million students diagnosed with a specific learning disability also have a related attention deficit disorder.

As computing learning opportunities expand across the country, my colleagues and I are exploring answers to a practical question: How do we make computer science (CS) more accessible and engaging for these students? Many of these learners will be, and already are enrolled in formal and informal CS learning opportunities. These students can be successful in learning CS if teachers are equipped to provide appropriate instruction and support to meet their learning needs.

In our NSF-supported work, we are: (a) reviewing Code.org’s Computer Science Principles (CSP) lessons for potential barriers to learning for students who learn differently; (b) starting with what is known from research in other subject areas about teacher practices supportive of students with learning differences and customizing those practices for CSP to pilot in a classroom at the Wolcott School in Chicago (an independent preparatory high school for students with diagnosed learning differences); (c) collecting data from students and the teacher about their experience with the adjusted lessons and (d) revising instructional approach suggestions for teachers to share with other CSP teachers and curriculum developers.

Several recurring curricular challenges identified by our team’s CS teacher and students in the first half of the CSP curriculum involve the following activities:

- learning new terminology (often as part of a lengthy presentation of information)

- reading and writing (which may occur as part of recurring class work, or formative and summative assessment activities)

- collaborating (that often takes the form of think-pair-share, paired programming, or partnered thinking and problem solving activities)

- discussing (either whole-class, teacher-led conversation, or within smaller group conversation)

- doing exploratory or project-based work (which is common throughout CSP lessons and part of summative assessments, often with little explanation or instruction)

- programming (prevalent in the CSP course)

Our preliminary research is finding that when some of our alternate instructional approaches are used during these activities, students who learn differently because of a learning or attention disorder can more easily access and engage in the CSP lesson activities. We’ve just now beginning to share some of these instructional recommendations for teachers to employ when they encounter these types of activities in the CSP class. Our team is excited to continue our research and share practical recommendations with teachers and curriculum developers more widely in the coming months. Learn more details about the University of Chicago's innovative research.

Dyslexic Children Programming: Overcoming Barriers Through Better Interaction

By Rob Thompson, Steve Tanimoto

There is a long history of computer-based solutions for students with learning disabilities to use for reading and mathematics [Hall et al 2000; Seo and Bryant 2009]. And yet, there is very little research on how learning disabilities affect computational thinking and general programming [Powell et al 2004]. Help Agent for Writing Knowledge (HAWK) is reading and writing instructional software for children with learning disabilities that’s been developed and tested for over five years. We then had the opportunity to expand HAWK to include programming. Our research questions included these:

- In what ways does dyslexia limit an individual’s ability to program?

- Can these limitations be circumvented through design?

- Will a synthesis between reading/writing and coding instruction help children learn?

We built Kokopelli’s World (KW) as an expansion onto HAWK. It is a blocks-based beginner coding environment organized into activities meant to teach basic concepts. The programs resemble standard English text and are framed as stories. Storytelling is used as a framing device and motivator for other programming environments. People remember story information better than plain text, [Willingham 2006] and it is more accessible than games for some students [Kelleher and Pausch 2007]. KW mimics English in that blocks form grammatically correct sentences. Commands are in third person declarative to match a storytelling style. Programs can be read aloud by the computer or shown as plain text.

We tested KW with students with dyslexia aged 7-12 years old. Students completed 85% of the activities they attempted. Students indicated that they liked coding and could use similar strategies for coding and writing. We plan to continue to study this.

References

Hall, T. E., Hughes, C. A., & Filbert, M. (2000). Computer assisted instruction in reading for students with learning disabilities: A research synthesis. Education and Treatment of Children, 23(2), 173 – 193.

Kelleher, C., & Pausch, R. (2007). Using storytelling to motivate programming. Communications of the ACM, 50(7), 58 – 64.

Powell, N., Moore, D., Gray, J., Finlay, J., & Reaney, J. (2004). Dyslexia and learning computer programming. Innovation in Teaching and Learning in Information and Computer Sciences, 3(2), 1 – 12.

Seo, Y., & Bryant D. (2009). Analysis of studies of the effects of computer-assisted instruction on the mathematics performance of students with learning disabilities. Computers and Education, 53(3), 913 – 928.

Willingham, D. T. (2006) Ask the cognitive scientist: The privileged status of story. American Federation of Teachers. Available here.

Working Group Summaries

Working groups focused on ways to improve the accessibility of materials. Summaries of these discussions can be found below.

Group 1: Learning Disabilities

Here is a list of strategies and questions that arise when thinking about students with learning disabilities.

- There is value about looking at what we know about instruction for students with learning disabilities in other disciplines. In math, we start from the concrete level, then representative, then abstract; we use schema-based problem solving, and strategies for mapping out problem. Scaffolded inquiry is used in science. Paraphrasing would apply to code reading just like reading other things. How we can apply that knowledge to computing?

- Facilitate direct communication between computer science (CS) and special education (SPED) researchers, CS teachers, and SPED teachers.

- Utilize strategies from computer science collaborative learning research to support more collaboration. What makes an effective group? How do you involve students with learning disabilities (LD) in groups? Thinking about things like scripted conversations and roles.

- Seek feedback from teachers implementing these curricula.

- What can be done to improve the level of rigor in LD CS research? How to share resources?

- What strengths can we leverage that LD students bring to the table?

- How can we impact our curriculum to benefit LD students? When the classroom is online?

- How can analytics data be leveraged and what to collect?

- Bring together different curricula to step towards a universally designed one.

- We would benefit from a way to search what is out there, standardized terms and stronger scientific rigor.

Group 2: Potential Non-Visual Projects

Many ideas were formulated for non-visual projects that all students regardless of disability can enjoy.

- Music Earsketch-like project

- Create an interesting radio show

- Create interesting music composition using music mixing

- Create Poetry- Haiku

- Build interesting chat bots

- Employ additional hardware, such as Talking Tactile Tablet, that are inherently accessible

- Create audio-animations such a demonstration of tree search

- Create Lego Robotics project using the technology developed by Stephanie Ludi [1]

- Some CS Unplugged activities can be modified to be non-visual (not coding project)

- Learning some basics of text analysis is inherently non-visual. Examples include computing edit distance, frequency table, and some basic text compression. Since Grade 2 Braille is compressed, learning how that can be automated could be done as a project.

- Hands on activities with Accessible Arduino might work.

- Tangible programming might work too such as SNAP circuits, Cubetto, and Torino.

- Smartphone and tablets have built-in screen readers that could be employed in projects. Accessible development environments are needed. The sensors on smart phones and tablets such as GPS, accelerometer, gyroscope and others could lead to interesting projects.

- Other possible projects might include Dot and Dash robots

- Blind people have built accessible games that can be found on RS-Games.

[1] Stephanie Ludi Ludi, Lindsey Ellis, and Scott Jordan. 2014. An accessible robotics programming environment for visually impaired users. In Proceedings of ASSETS ‘14: International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers & Accessibility. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 237-238. http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2661334.2661385

Group 3: Accessible Classroom/Teaching

A number of ideas arose when discussing the accessible classroom and accessible teaching.

- Use accessible web-based products to structure classroom discussion and interaction.

- Teach accessibility as an important topic. The Teach Access website has a tutorial. There is also an excellent accessible web design course at the AccessComputing website.

- Universal design such as captioned video, alternative assessments, alternative explanations of concepts, clear directions, posting notes and slides, and scaffolding for assignments.

- Audio description for video.

- Statewide initiatives may be necessary to make sure the new CS course are mandated to be accessible

- Work with organizations that teach CS such as Project Lead the Way, TEALS, Teach for America, and others to help their teachers teach in an accessible way.

Group 4: Making Blocks Accessible

Block languages are currently not accessible to screen reader users. Some alternative ideas were discussed.

- Non-visual ways are needed to convey information, speech and haptics perhaps.

- Tangible blocks might be useful like in Osmo.

- Some tangible products for blind students already exist: Torino.

- Support programming without syntax errors such as in Accessible Blockly.

Group 5: Supporting skills other than coding

Computer science is not just coding. It requires the understanding of many topics. Questions posted by this group included; how can we make:

- data and data analysis accessible?

- graphs and charts accessible?

- animations and demonstrations accessible?

- basic problem solving accessible?

Communities of Practice

AccessCSForAll engages stakeholders that include national leaders within Communities of Practice (CoPs). CoPs share perspectives and expertise and identify practices that promote the participation of people with disabilities in STEM fields. Those most related to AccessCSForAll are described below.

Broadening Participation CoP

In this CoP, individuals who administer projects that serve to broaden participation in STEM fields

- discuss how to recruit participants with disabilities and accommodate them in their programs and activities and how to make their offerings more accessible overall

- recruit their participants with disabilities into disability-related e-mentoring, internships, academies, and workshops to complement their activities

- co-sponsor events and discuss potential new projects and share funding possibilities

Computing Faculty, Administrators, and Employers CoP

Computing professionals, faculty, and administrators as well as representatives from industry and professional organizations use this CoP to increase their knowledge about disabilities and make changes in computing departments that lead to more inclusive practices. Participants

- gain and share knowledge and help identify issues related to the underrepresentation of people with disabilities in computing fields;

- help identify and field test Computing Department Accessibility Indicators to make computing departments more welcoming and accessible to students with disabilities;

- help organizations make their websites accessible to visitors with disabilities, their conferences accessible to attendees with disabilities, and their conference programs inclusive of disability-related topics;

- identify campus computing events to which students with disabilities might be invited; and

- discuss how to include accessibility topics in postsecondary computing curriculum.

You and your colleagues can join CoPs by sending the following information to doit@uw.edu:

CoP(s) you would like to join

- name

- position/title

- institution

- postal address

- email address

For information about other CoPs affiliated with AccessCSForAll, consult our partner program AccessComputing.

Resources

The AccessCSforAll website contains:

- information about project goals, objectives, activities, and project partners

- evidence-based practices that support project goals and objectives

- resources for students with disabilities

- educational materials for teachers and administration

AccessCSforAll maintains a searchable database of frequently asked questions, case studies, and promising practices related to how educators can fully include students with disabilities in computing activities. The Knowledge Base can be accessed by following the “Search Knowledge Base” link on the AccessCSforAll website.

The Knowledge Base is an excellent resource for ideas that can be implemented in computing programs in order to better serve students with disabilities. In particular, the promising practices articles serve to spread the word about practices that show evidence of improving the participation of people with disabilities in computing.

Examples of Knowledge Base questions include the following:

- What are specific computer applications that can assist students with learning disabilities?

- How can K-12 educators promote the use of accessible technology in schools?

- Are there any web-based tutorials on accessibility?

- How can principles of universal design be used to construct a computer lab?

- How can K-12 computing instructors get support working with students with disabilities?

Individuals and organizations are encouraged to propose questions and answers, case studies, and promising practices. Contributions and suggestions can be sent to AccessCSForAll@uw.edu.

For more information on AccessCSforAll, universal design, and accessible computing education, review the following websites, videos, and brochures.

- Find more information on universal design in education, visit the Center for Universal Design website.

- Learn more about and get involved with AccessCSForAll.

- Discover ways to encourage students with disabilities to pursue computing and how to create an accessible inclusive environment for them, view AccessCSForAll videos.

- Read more discussions and presentations on including students with disabilities in ECS and CSP courses, Increasing the Participation of Students with Disabilities in Exploring Computer Science and Computer Science Principles Courses.

- Learn more about accessible programming, explore Quorum.

- Learn more about and to get involved with a similar project, AccessComputing.

- To read profiles of computing professionals and students with disabilities, visit the Choose Computing profiles.

Acknowledgments

AccessCSForAll capacity building activities are funded by the National Science Foundation (Grant #CNS1440843). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the CBI presenters and publication authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

DO-IT

University of Washington

Box 354842

Seattle, WA 98195-4842

AccessCSForAll@uw.edu

www.uw.edu/accesscomputing/AccessCSForAll

206-685-DOIT (3648) (voice/TTY)

888-972-DOIT (3648) (toll free voice/TTY)

206-221-4171 (FAX)

509-328-9331 (voice/TTY) Spokane

AccessCSForAll Principal Investigators: Richard E. Ladner, Ph.D. and Andreas Stefik, Ph.D.

Co-Principal investigator: Sheryl Burgstahler, Ph.D.

© 2017 University of Washington. Permission is granted to copy this publication for educational, noncommercial purposes, provided the source is acknowledged.