What Models, Approaches Or Frameworks Exist In The Field Of Disability, ICT, And Post-Secondary Education; Are They Successful In Transforming The Support And Delivery Of ICT For Disabled Students Or Do We Need New Ones?

By Jane Seale, The Open University, United Kingdom

The Leverhulme Trust has funded the International Network on ICT, Disability, Post-secondary Education and Employment (Ed-ICT) to find areas of research related to the network’s focus areas, specifically, the role that information and communication technologies (ICTs)—including computers, mobile devices, assistive technologies, online learning, and social networking sites—play or could play in creating barriers and mitigating disadvantages that students with disabilities experience in post-compulsory/post-secondary education both generally and specifically in relation to social, emotional and educational outcomes.

Practitioners in post-secondary education generally know they need to be more inclusive in their educational practices; however, awareness doesn’t always result in successful practice. Models and frameworks can work as tools to guide practitioners, as long as we are critical of these models and frameworks.

In my paper of the same name as this presentation, I focus on nine different models or frameworks, most of which focus on accessibility. All fall within or across the following three areas:

- Micro Level—A focus on practices involved in making all resources and activities accessible (e.g., Universal Design, the Holistic Model)

- Meso Level—A focus on the delivery of services within an institution that play a role in promoting the use of supportive ICTs and contribute to successful educational and employment outcomes (e.g., Staff Development Model for Inclusive Learning and Teaching)

- Macro Level—A focus on the institution where those services and practices take place, including the internal and external factors that influence institutional development and organization (e.g., The Model of Professionalism)

Furthermore, we must ask how these models and frameworks transform practice. How valid and efficacious are these models and frameworks? Have we carefully examined the validity and efficacy or are we blindly following others? Have we considered all options?

All models and frameworks should be carefully examined for validity and efficacy, including the writings and work that underpin each model. For validity, we can ask the following questions:

- How were the models or frameworks derived?

- What evidence is there that they have improved practice or outcomes for students with disabilities?

- For efficacy, we can ask the following questions:

- How detailed are the models or frameworks- what is their level of granularity?

- Have the models and frameworks been implemented in practice? How widely have they been implemented?

Often models are criticized in a superficial manner, or, transversely, are championed without acknowledging their weaknesses. Is there really only one model or framework that can do the job, or do we need multiple models and frameworks? And, are we applying the right critical lens when analyzing these models?

Questions and comments from the audience included the following:

- What research is already being done for models?

- Different backgrounds will create different models, and so if all models are coming from the same place, they may not fit for everyone.

- Can we have a large broad model that covers everything and then work backwards to cover the granularity as needed?

- The value of a model has to do with the hypothesis that it can be used to test—for these models, there hasn’t been much testing or practice.

- People don’t always know what model they are using.

- The cost of applying each model should be taken into account.

- Each model could have a range of options to be used for different problems.

- One problem can have multiple solutions—for example, all buildings can have ramps or all people could be given a flying wheelchair. Cost and ease of use must be considered.

- When choosing a model, unconscious bias should be reviewed. For example, a professor may think they know best about disability and choose a model based on their own experiences; however, it may be inappropriate for students with disabilities.

- What outcomes do we value? Policymakers and educators will want different outcomes and may value different results than other stakeholders.

- How are different researchers and practitioners considered in a model?

How Design Frameworks and Models Have Informed My Work

By Sheryl Burgstahler

At the University of Washington, we have two centers under Accessible Technology Services, the Access Technology Center funded specifically for the UW, and the DO-IT (Disabilities, Opportunities, Internetworking and Technology) Center, which is funded by the state and various national and international grants. Universal design (UD) informs much of my work. UD can be viewed as an attitude, a framework, a goal, and a process. UD values diversity, equity, and inclusion; promotes best practices; works proactively; and minimizes the need for further specialization or accommodations.

Universal design can be applied to physical spaces, instruction, services, and ICT. Universal design is defined as “the design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design.” (The Center for Universal Design). Software and web applications should be designed for use by individuals with disabilities, including those who use assistive technology. Accessible design strategies include keyboard-only design, alternative text, descriptive links, hierarchical structure, and captioned videos.

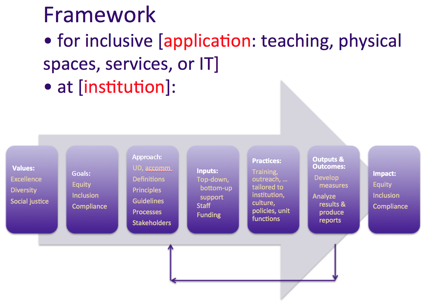

UD works as a framework as indicated in the following image that is described to the right.

Any application of the UD framework is built on key aspects of the environment in which it is being applied. These potentially include the following:

- Values: e.g., social justice model of disability; inclusion of diversity, equity, and inclusion

- Goals: e.g., equity, inclusion, compliance

- The Approach: e.g. universal design vs accommodations that rely on definitions, principles, guidelines, processes and stakeholders

- Inputs: e.g., those that are top down and those that are bottom-up; staffing levels, and funding

- Practices: e.g., training, outreach, etc., that is tailored to in the institution, culture, policies, and unit functions

- Outputs and Outcomes: that require developing measures, analyzing results, and writing reports

- Impacts: to include equity, inclusion, compliance as established with the original goals

Research on UD of ICT often employs a usability testing design approach. CAST has done research on the universal design of learning, although most of the research has been conducted at an elementary grade level and in language arts, with interventions not always tested with students with a wide variety of characteristics that include disabilities. In one chapter of the second edition of Universal Design in Higher Education: From Principles to Practice, research 19 studies of universal design of instruction at the postsecondary level are reported; most looked at the average success/satisfaction of students overall. DO-IT through a quasi-experimental design showed that post-secondary students with disabilities in classes with universal design for instruction-trained instructors earned grades closer to those of students without disabilities. Read more about the study here.

What ICT design should be addressed with UD, and what should be addressed with assistive technology and other accommodations is an ongoing question in the field of ICT?

Some of the questions and responses of the participants are captured below.

- What are the challenges in the future in terms of UD of learning?

Getting people to actually do it is the hardest part of the framework. Faculty and staff must be trained and have support, which requires time and funding. Many faculty members have not heard about UD or know it is an option for their teaching practices. - The EPUB (a file type) standard strongly supports accessibility for digital tools. However, disability resource services are not ready to deal with EPUB. What is the solution?

Disability resource services and IT departments need to work together to adopt new, powerful, and inclusive technology. - How do we get administrators and other stakeholders involved?

At the UW, in a top-down effort we secured the support of the chief information officer for our goal to improve IT accessibility campus-wide. We have also worked bottom-up by enlisting a volunteer group of IT Accessibility Liaisons representing different departments signed on to meet a few times a year, engage in discussions about accessibility, and promote accessibility in their units and beyond. However, much work remains to be done before IT is fully accessible to all of our students. - What is Washington State Policy #188?

It sets the expectation that all state agencies will develop, procure, and use IT that is accessible to everyone, including those with disabilities. Learn more about Policy #188 at ocio.wa.gov/policy/accessibility. - How can we test to make sure UD of learning is working?

It’s hard since it’s such a broad topic, and all testing will be very specific. We have many promising practices, but we don’t know if we can say they’re testing or research. - How do you work with third party vendors and accessibility?

Our most successful practice was when I asked to do a co-presentation with one of our main procurement people at a procurement conference. That got him very interested in accessibility, which led him to supporting more accessibility in our purchases.